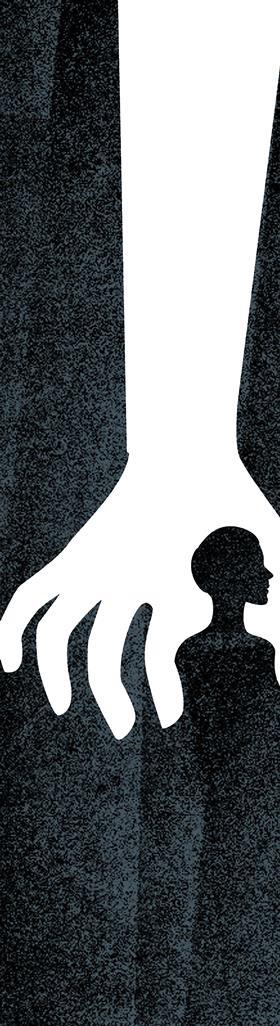

As the SRA takes an increasingly tough line on sexual misconduct in the profession, Andrew Katzen sets out what law firms should know about the regulator’s investigatory process

Few people working in law firm risk management will be unaware of the seriousness with which the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) now takes the issue of sexual misconduct.

Identified as a ‘key theme’ in each of its last four annual “Upholding Professional Standards” reviews, in September the SRA issued new guidance on how it expects solicitors and law firms to behave in relation to sexual matters.

A press release accompanying the guidance revealed the regulator had received 251 complaints of alleged sexual misconduct over the previous five years and had 117 ongoing investigations. This, plus its proposal in August to punish sexual offences with fines only in “exceptional circumstances”, should make it clear that solicitor behaviour – and, by extension, law firm culture – is under scrutiny like never before.

Everyone involved in law firm risk management needs to understand the process by which the SRA investigates these allegations, and the steps needed to comply with the regulator while best protecting the positions of everyone concerned.

The SRA definition of sexual misconduct

The SRA’s definition of what constitutes sexual misconduct is widely drawn. The September guidance does not outline every behaviour that may constitute a breach, preferring instead to refer to solicitors’ obligations to adhere to the SRA Principles:

- Principle 5 (act with integrity)

- Principle 2 (act in way that upholds public trust), and

- Principle 6 (act to encourage equality, diversity and inclusion).

However, it does give some detailed illustrations of behaviour which the SRA will treat as a regulatory issue.

The new guidance builds on the SRA’s “Upholding Professional Standards” document for the financial year 2020/21, published in July 2022, which defined sexual misconduct as including “sending inappropriate messages, making inappropriate comments, non-consensual physical contact and sexual assault”.

The document explains that these offences, “can arise in the working environment, at work-related social events or in the solicitor’s private life”. The question of how the physical location in which the behaviour takes place might impact its seriousness is addressed in the September guidance, which also says solicitors, “must not abuse their professional position to initiate or pursue an improper sexual or emotional relationship or encounter with a client, a colleague or anyone else”.

Initial steps toward investigation

An investigation may start following a report by an alleged victim of sexual misconduct (which could be an employee of a law firm or a client) or a self-report from the accused solicitor in question or their law firm.

Precisely when it is appropriate to self-report an allegation of sexual misconduct to the SRA is case dependent, but in general terms if a client or colleague reports they have been a victim of sexual misconduct then the firm’s compliance officer for legal practice (COLP) is obliged to report it.

Having decided to investigate, the SRA will appoint an investigator to the case. They have the power to require attendance at interviews, to request the provision of information and documents, and to attend a law firm’s office without notice.

In most circumstances, an investigator’s first action will be to inform the subject that the investigation is taking place; the only exception to this being when the SRA considers that informing the subject may prejudice its investigation.

After informing the subject of the fact of the investigation, the investigator’s next action may appear to be nothing at all.

The SRA, like most other regulators and publicly funded investigatory agencies, struggles to handle a large amount of casework on a limited budget. In March, the SRA revealed that the median length of time for one of its investigations was 320 days while the median average time before an investigated matter was issued to the SDT was 28 months.

If it is determined that the alleged behaviour does not present an immediate further risk to others the investigator may pause an investigation until they have the time and resources to take it on properly.

In any case, law firms should, on being informed of an investigation, appoint a senior individual - such as the COLP - to act as primary liaison point with the SRA. This individual, who may work with administrative assistance, should ensure all communications with the regulator are professional, courteous and timely.

Internal investigations

A law firm which is made aware of an allegation of sexual misconduct should carefully consider commissioning an internal investigation into the matter. Even aside from the strong ethical and governance reasons for doing so, an internal investigation into the matter can be a powerful benefit to a law firm when dealing with the SRA.

As well an enabling the firm to collect, preserve and analyse relevant evidence, and deciding if any remedial action is required, a properly conducted internal investigation will enable the firm to understand whether it bears any corporate responsibility for an individual’s conduct.

Internal investigations must be thorough and independent. If the allegation is against a junior staff member, then this may be achieved with an investigation overseen by someone internal such as a partner. However, if the allegation is against a senior lawyer - and certainly if against a partner – then the investigation may be better conducted by an independent outsider.

Engaging with the SRA

The SRA’s information-gathering process into an allegation of sexual misconduct can be a drawn-out process involving multiple rounds of questions, posed both in writing and at face-to-face interviews. The agency will likely also request specific documentation.

The SRA will usually impose tight deadlines on its requests – often only 14 days – which may (depending in circumstances) be extendable, on request.

Law firms and their employees are obliged to co-operate with the SRA in relation to its inquiries. Failure to do so is misconduct. Aside from adhering to its duty to engage, a law firm may benefit from adopting a proactive and responsive attitude to SRA investigations.

A well-prepared firm may, for example, be able to use this initial investigatory period to make representations to the SRA about whether a case should proceed. Timely presentation of evidence, gleaned from an internal investigation, which show why an investigation may be unmerited may enable the regulator to recognise that a case should be dropped.

Regulating culture

The SRA’s new sexual misconduct guidance is clear about how it expects firms to act in these cases. “We expect firms to foster a culture of zero tolerance of sexual misconduct”, it states, “where staff feel they can speak up freely and report matters to their firm and to us. Any allegation of sexual harassment in the workplace presents an issue firms will need to investigate sensitively and appropriately in compliance with their legal and regulatory obligations.”

What’s next?

In November 2020 the High Court ruled against the SRA in an appeal case brought by former Freshfields partner Ryan Beckwith against the SDT’s decision to sanction him for a disputed sexual encounter with a junior colleague.

The High Court ruled that for sexual misconduct cases that had not resulted in criminal convictions, disciplinary findings should only occur when there is a clear link to, and resultant breach of, the SRA’s code and principles.

The new guidance gives detailed examples of circumstances and situations in which the SRA alleges that link and those breaches can be made out.

Introducing the guidance, Paul Philip, the SRA’s chief executive, said: “We take reports of sexual misconduct seriously. These can be sensitive and difficult issues and we want to be clear about our expectations, not least for firms, as people often come to us because they are dissatisfied with the way their firm has dealt with their concerns.

“Importantly, as we said in 2020, the Beckwith judgment made it clear that it was ‘common sense’ that upholding our principles of acting with integrity could reach into a solicitor’s private life.”

The SRA’s direction of travel in sexual misconduct matters is clear. The agency is more concerned about issues like sexual behaviour, harassment and bullying than ever before. Law firms should prepare for many more investigations into these matters in the future.