The Law Commission’s long-awaited report, Modernising Wills Law, was published in May. Laura Abbott examines the main proposed reforms

On 16 May 2025, the Law Commission announced the results of its modernising wills project, proposing reforms to ensure the law relating to the preparation of wills is “fit for purpose in the modern age”, alongside a draft bill for an entirely new Wills Act.

Reasons for reform

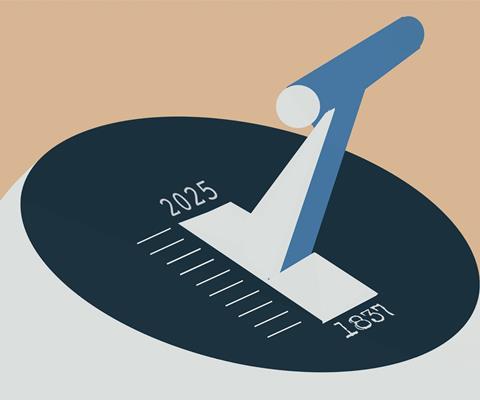

As the current Wills Act dates to 1837 – the year Queen Victoria came to the throne, nearly 200 years ago – few could argue that reform is not long overdue. Modern society is unrecognisable from that of the Victorian age, with people living longer, in more complex family structures, with large estates and increasing health issues. We also now live in the digital age.

With two-thirds of the adult population not having a will, and with disputed estates on the rise, the purpose of the reforms is to make wills more accessible and remove some of the key reasons for disputes after death.

Although the Law Commission’s report was long in the making – the project has been ongoing since 2016 – it was certainly no anticlimax; the review is comprehensive and the proposed reforms are bold, and the commission has not shied away from tackling some of the more contentious areas. If all the proposals are implemented, the wills and probate landscape is set to change significantly.

However, the reforms remain at the proposal stage only, and it’s now for the government to consider and respond to the recommendations. An interim response is due within six months of the publication of the report, and a full response within a year.

Key proposals

The key proposals include the following:

Marriage should not revoke a will

Under the current law, a person’s will is automatically revoked if they get married or form a civil partnership. The report recommends abolishing this rule to resolve the increasing problem of predatory marriage – where someone marries a person in order to inherit from them – as a form of financial abuse. The argument against is that spouses may not then inherit because an earlier will has not been revoked, although there is scope for them to bring a claim for financial provision pursuant to the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975.

Support for electronic wills

The report recommends making provision to introduce electronic wills, although it emphasises that appropriate safeguards must be in place. This is probably the most controversial of the proposals. Although the need to modernise is clear, financial abuse of the elderly and vulnerable is already increasing and so sufficient protection does need to be carefully considered.

The commission’s report does not prescribe specific technologies or methods to make electronic wills (to allow for innovation and technological advances) but rather outlines the principles that must be met. This includes secure signatures, witnessing protocol, reliable storage, and proper authentication. The commission emphasised that electronic wills should be treated no differently than physical wills in terms of the process of proving them and the burden of proof required to demonstrate validity.

Clarification on testamentary capacity

The report recommends that the test for testamentary capacity should be in line with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), as for all other capacity decisions. Confusion over whether the existing test in Banks v Goodfellow (1870) LR 5 QB 549 or the MCA should apply has been a consistent theme in most capacity cases since the MCA’s introduction, so clarification is welcome. However, it will make capacity assessment at the point of will-making more onerous and so potentially more costly, which would conversely have the opposite effect the reforms are trying to achieve. This is looked at in more detail in the article in this issue, All change for capacity?.

Lowering the age for making wills

The report also suggests lowering the age a person can make a will from 18 to 16. The aim here is to eliminate injustices that can arise where a child dies and the distribution of their estate is governed by the statutory intestacy provisions, which may not be according to their wishes.

Courts can infer undue influence

To provide better protection to elderly and vulnerable testators, the report recommends that it should be possible for the courts to infer that a will was brought about by undue influence. This is a welcome development: currently such cases are rare because undue influence is so difficult to prove, which means it’s easier for it to happen and to go unchallenged. This also brings undue influence in the preparation of a will on more of an equal footing with undue influence in respect of lifetime gifts where there is a presumption of undue influence.

Courts can ratify a will

The report recommends allowing the courts to prove wills in exceptional circumstances, for example where the court is satisfied that a will exists which represents the testator’s wishes, even if the will was not finalised in time or did not comply with the current formality requirements. On the one hand, such flexibility seems sensible in situations of premature death, say before a planned will signing or where a will fails due to non-compliance with the prescribed execution and witnessing formalities. On the other hand, the current formalities are there for good reason (to protect elderly and vulnerable testators) and this may open the floodgates to all sorts of spurious disputes regarding incomplete wills.

Further proposals

These are the headline reforms, but there are also lots of other smaller reforms proposed on things like, for example, who can act as witnesses to wills, who can sign on a testator’s behalf and some amendments to the law on when a will can be rectified (corrected in the case of errors) and where gifts adeem (where they fail if they no longer form part of a testator’s estate on death).

Response to the report

In the government’s official response, it stated that it welcomes the Law Commission’s report, noting the proposed reforms are significant and wide ranging and deserve detailed consideration, and acknowledging “… the current law is outdated, and we must embrace change …”. However, it’s still not clear which, if any, changes may be implemented, so practitioners are unable to realistically prepare for the future.

Overall, change appears to be widely supported in the profession. STEP, the global professional body for practitioners in the fields of trusts, estates and related areas, says: “The reforms will modernise the law to support testamentary freedom, protecting testators and increasing clarity and certainty in the law.”

However, it remains to be seen whether it’s possible to modernise while maintaining protection. The issues are complex and practitioners are cautious, because the danger is that we solve one problem by simply replacing it with another.