In the third of our series on outsourcing for law firms, Kerry Underwood considers the benefits of offshoring legal work, and outlines his firm’s approach

In my last article in Managing for Success (‘Remote control’, May 2015), I looked at the offshoring / outsourcing of back-office functions. Here, I look at the same process, but in relation to actual legal work, rather than so-called support work.

Outsourcing is something with which law firms are very familiar. Commonly outsourced tasks include costs-drafting, process serving, bookkeeping, statement-taking and attending suspects at police stations. You might be surprised to learn that instructing counsel is another classic example of outsourcing. The reasons are the same as for many other types of outsourcing: it is cheaper for us (to have counsel in court than one of our own staff); the fee is lower to the client; the quality is assured (as counsel are doing their core business – they are in court every day); and it is more efficient (we do not need a full-time advocate – we can use counsel as and when we want).

Whether one agrees or disagrees with this thinking, it has been adopted by very many law firms.

In this article, I consider outsourcing legal work to a cheaper jurisdiction, generally known as ‘offshoring’: that is, sending legal work to another country which has lower costs.

The argument for offshoring

What is remarkable to me is not my long-held belief that offshoring will become a common way of delivering legal services, but rather that it has taken this long for the idea to gain recognition.

So why has this area received scant attention until now?

First, until recently, legal services could not be delivered quickly enough through offshoring, because communication methods were not speedy enough. Material goods – commodities – could be picked or manufactured and stored until someone wanted to purchase them. Even for tailor-made goods, time was not normally of the essence. With legal services, it always is. Now, the speedy, economical and reliable transmission of large amounts of written material has been made possible by more reliable email and internet connections.

Second, and perhaps most significantly, the law has been, and to a certain extent remains, a cottage industry run by owner-managers. A person owning a shoe factory will not actually be making the shoes, but a person owning a law firm will generally be doing legal work. The factory owner who moves production to a cheaper jurisdiction is unlikely to feel that their job, career or profession is threatened. A lawyer running a law firm will always have mixed feelings about putting legal work abroad.

But consider the advantages to that shoe manufacturer – lower costs, greater profit, fewer labour disputes – and it’s unsurprising that offshoring is now the norm in manufacturing. As you read this, you are likely to be wearing clothes and shoes made in a cheaper jurisdiction, checking your email on a mobile phone or tablet made overseas, and, if your concentration wavers, you may be thinking about what to watch later on your foreign-made television, or where you will be driving in your non-UK produced car.

While it may be true that if you want coffee or coconuts, tea or turmeric, these have to be imported, because they are not easy to grow in Britain, all of the other items listed above could be, and used to be, made in Britain. The only reason why they are now imported is that it is cheaper to manufacture the goods abroad and bring them to this country, even taking into account the cost of physically transporting them.

Intellectual services involve no such financial or environmental costs, so the economic case for offshoring such services is even more compelling. Whatever you think of EU and UK employment laws, the regulatory and red-tape burden is enormous. Much of this is avoided by offshoring work.

In addition, if you pick the right areas of work and manage the process effectively, quality can easily be maintained The reality is that most road traffic fixed-costs work is carried out by unqualified clerks on relatively high salaries given their qualifications, or lack of them. Staff of similar or higher quality can be employed at under half of the cost in, for example, South Africa.

Setting up

So you are considering offshoring some of your legal work, but where do you start?

The first decision to be made is whether the firm sets up its own operation abroad, or works through an existing organisation. I dealt with the day-to-day practicalities of these choices in my last article.

The next question is what type of business structure to choose. Inevitably, work will be done in other jurisdictions – that is the whole point – so a limited company or plc is likely to be a better vehicle than a traditional partnership, or LLP. Realistically, most firms looking to offshore will not have the knowledge, experience or resources to set up an office abroad, but will instead work through one of the existing operations. The firm can choose to have everything going out on its own notepaper, or that of the offshoring company, provided the offshoring company is a recognised body.

What work to offshore

Pre-issue civil litigation work can be done by anyone for gain, as can all employment tribunal work.

Statistically, the vast majority of civil litigation work involves either fixed costs or no recoverable costs. Over four million portal claims have now been issued since the first portal came in on 30 April 2010. Fixed recoverable costs mean just that: the recoverable costs are fixed. Consequently, the key to profitability is how much it costs to do the work; there is no higher fee for a more experienced and expensive lawyer. This brings legal fees into line with material goods. They are sold at a pre-determined price, and the trick of the business is to produce the service within that budget. So all of the points I made earlier about imported goods apply to areas where fixed recoverable costs apply. Damages-based agreements and contingency fees are a form of fixed fee. The one thing that all commentators agree on is that fixed recoverable costs will spread both horizontally – that is, to other areas of civil work – and vertically – that is, upwards beyond the current upper damages limit of £25,000. The current plan is to spread fixed recoverable costs to all civil work, and the new ceiling being considered is £250,000. That would cover virtually all civil cases in England and Wales.

Much non-contentious work is also often already carried out on a fixed fee basis – for example, conveyancing, wills and lasting powers of attorney.

Different considerations apply to other upper end multi-track work. Guideline hourly rates exist for every part of England and Wales, covering a variety of levels of fee-earner, but that leaves unanswered the rate for, say, a 10-year qualified attorney working in Cape Town for an English recognised body on a complex clinical negligence case. The danger is that a lower rate will be allowed to reflect the lower cost base, but that defeats the purpose of the exercise.

This will change, but in the meantime, it needs to be recognised that work being offshored will lead to an overall reduction in legal fees, although it should still allow enterprising firms to cut fees and increase profit margins, a virtuous circle if ever there was one.

Turn the clock forward a few years. Consider your response to a costs officer stating that the 200 hours of document review and so on you firm has done could – and should – have been carried out in South Africa or India, for example, at a lower cost, and therefore your fees for that aspect of the work will be halved. It will happen!

Note also that firms currently carrying out defence personal injury work for insurance companies are generally doing so for low hourly rates – they have nothing to lose by all work going abroad, even if the ‘guideline’ rates are halved.

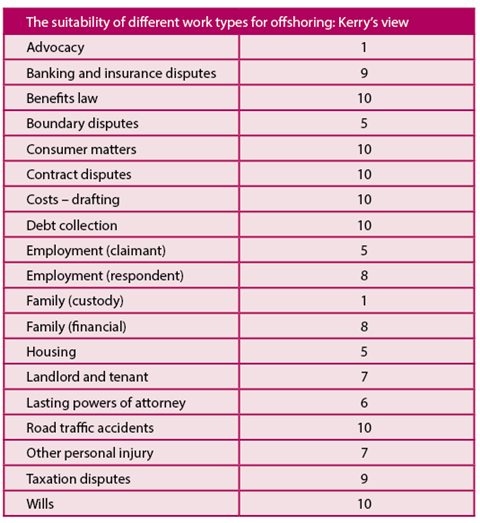

In the table [opposite], I set out various work types and rated them, based on my own opinions, as to their suitability for offshoring, on a scale of 1 to 10. 1 means that it is very difficult to offshore such work, and 10 means ‘why is it still being done here?’

Factors in the evaluation include face-to-face time with the client, client perception of the outsourcing of that service, required court appearances, offshore lawyers’ understanding of the legal issues at hand, how much local knowledge is required (such as planning issues), and the sensitivity of the case (such as matters involving child custody).

A case study: how we do portal work in South Africa

Leah Waller, partner at Underwoods Solicitors, sets out how our firm uses South Africa to conduct portal work.

‘It is this firm’s policy to see every single client; whether that means attending the client at their home or the client attending our office, we will see every client at an initial meeting to take a full statement from them.

This initial appointment is undertaken by a trainee solicitor for all portal work, and a full and detailed witness statement is taken from the client and prepared by the trainee solicitor.

The trainee solicitor will dictate their note of the meeting and the witness statement, and send this to our office, run by Doné Barnard, in Wellington, South Africa.

From the dictated attendance note and witness statement, the staff in South Africa are then able to prepare stage one of the portal claim.

Each member of staff in South Africa is able to log on to the portal and create a new claim on it, inserting all of the information provided in the attendance note of the trainee’s meeting with the client.

The staff in South Africa will send a note back to the trainee who saw the client to let them know that the claim has been drafted in the portal and is ready for consideration. At that point, if any information necessary to process the application is missing from the attendance note and witness statement, they will also request that the trainee send them that information.

The trainee solicitor will then either request that information and send it back to the staff in South Africa, or, if all information has already been obtained and the claim is ready for review, they will check through the claim and send it to their client for their approval and signature before submitting it to the insurer. However, we are now increasingly conducting this stage from South Africa; phone calls during the day from South Africa to England are of minimal cost.’

Doné Barnard, our office manager in Wellington, sets out how other firms use our service to do portal work.

‘All of the staff here in South Africa are fluent in English and are happy to speak with clients, and this is advantageous for those firms who do not see all of their clients.

The staff here are able to telephone the client and take a statement from them in relation to the accident and injuries, and use this to complete stage one of the portal claim.

The note of our telephone conversation is then sent to the case manager, and the fee-earner is advised that the claim is drafted and on the portal for their consideration.

We can take an active role in sending the draft claim to the client for their approval if we are asked to, or this can be done by the case manager.

The portal is accessible by our staff in South Africa and the fee-earner who has given us the client, and so it works seamlessly.’

Client attitudes

Underwoods Solicitors surveyed all of our clients on the issue of us sending their work to South Africa. 81% of those who responded were happy for the work to go abroad, on the basis that there would be some cost benefit to them.

In many cases, nobody from a law firm now ever meets a client. It is a paper, case-managed transaction, with the client normally referred by a claims management company, or trade union, or insurance company. If you live in London and your paralegal is in Manchester or Liverpool, they may as well be in Mumbai or Durban. Because of our sensitivities towards this issue, we have Skype links between our operations in Cape Town and England, and clients can access this system free of charge through us, which is probably a rather closer relationship than if the case was being handled in England or Wales!

Firms offshoring their work can also make sure that documentation is easily accessible to their clients, as well as their lawyers, in both countries, by using digital dictation and emailing the voice files for typing cheaply offshore, and then holding the files electronically for instant, secure, 24/7 access online. I addressed the practicalities of this approach in my first article.

Potential problems

You may be concerned about professional indemnity insurance, but this really isn’t a problem. Indeed, insurers welcome firms who are looking to the future. We have never had an issue with it.

With the widespread use of telephone hearings for all but the trial, even the more obvious problem of advocacy has become much more manageable. For the trial itself, most law firms instruct counsel, and that will not change. Solicitor-advocates can perform the same function as counsel. Advocates will be at a premium, as that is the one aspect of legal services – appearing in court – that will still be reserved to lawyers, even when everything else becomes a free-for-all.

Firms will also, naturally, be concerned about quality control. However, the reality is that much low value work – for instance, most road traffic fixed-costs work – is carried out by unqualified clerks on relatively high salaries given their qualifications, or lack of them. Staff of similar or higher quality can be employed at under half of the cost in, for example, South Africa.

Having said this, I would caution you to be wary of prioritising only low costs in terms of labour. Legal process outsourcing, and indeed business process outsourcing generally, is a priority of the government of the Republic of South Africa, and has its full support. It has the ability to create sustainable jobs that have no adverse impact on the environment, and do not involve the exploitation of finite mineral or other wealth. This is also true of many other countries. Firms should consider these matters before offshoring but lower labour costs in a cheaper jurisdiction do not translate into cheap labour in that country.