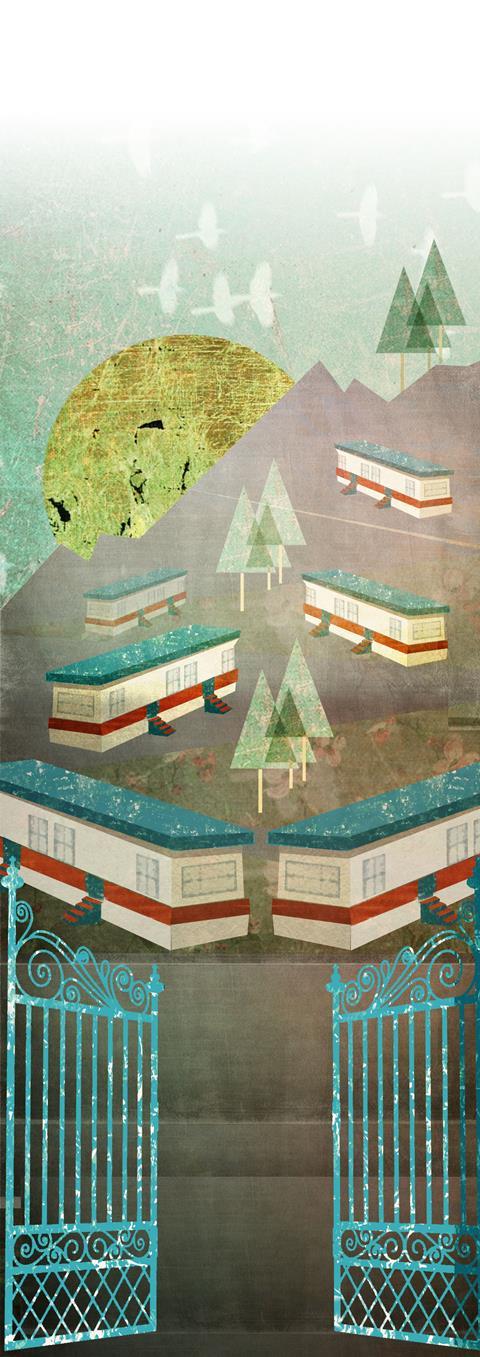

The Mobile Homes Act 2013 introduced a new compulsory system for the buying and selling of mobile homes. Neil Miller provides a beginner’s guide to the act and what it means for this small, but important, community – and those who advise them

Most conveyancers and property specialists will have come across mobile homes (better known as ‘park homes’) and their idiosyncrasies at one time or another.

Unlike bricks and mortar, park homes do not constitute ‘real property’. Instead, they are chattels which can be bought and sold as you would a car. Where they differ from cars and other chattels is in their fixed situation: they are ‘stationed’ on ‘pitches’ in mobile home parks which, thanks to the Mobile Homes Act 1983 (MHA 1983), confer rights and obligations as between the resident (occupier) and the park owner. These rights and obligations are enshrined in a document known as a “written statement”. Thus, an occupier of a park home on a “protected site” (one to which the MHA 1983 applies) obtains a measure of security of tenure and, in theory at least, cannot be evicted unless they breach a term of the written statement.

In practice, the abuse of occupiers’ rights has been commonplace for decades, and sufficiently widespread to alienate a large proportion of those who might otherwise be attracted to park homes as a lifestyle option.

The act does not apply to holiday homes. By a combination of planning and site licensing enquiries, the true position can be established – a soul-destroying exercise, but an absolutely necessary one

It is this abuse, and in particular the practice of ‘sale blocking’ (systematic attempts by park owners to deter prospective purchasers of a park home) that resulted in the Mobile Homes Act 2013 (MHA 2013), which introduced the first ever compulsory system to facilitate the buying and selling of park homes. The new act represents a significant revolution in a small community. In this article, I explain how it works and consider how effective the new system has been in the 10 months since its inception.

What does the new act do?

Parliament set itself an ambitious task when it set out to draft, from scratch, this new system. No system existed previously, so it was not a question of learning from past mistakes or adding to an existing structure. After a period of consultation, the new system had to be concocted as a stand-alone mechanism to enable park homes to be bought and sold effectively, promptly and without undue complexity.

Before the new system was introduced in May 2013, park homes were, more often than not, bought and sold as one would a second-hand car. The only documentation exchanged would be the written statement, which was passed from seller to buyer at completion. No contract would be prepared, enquiries raised or searches made.

Despite this, there are very many occupiers who live happily and contentedly in their park homes across the UK. But it will surprise no one with a legal background to learn that there is also a significant minority whose lives have been turned upside down, or even ruined, as a result of stumbling blindly into park home ownership.

The act does not apply to holiday homes. By a combination of planning and site licensing enquiries (all mobile home parks must be licensed by the local council), the true position can be established. This can be a soul-destroying exercise, but an absolutely necessary one.

How does it work?

The new system calls for the preparation of schedules of information and notices, and the provision of documentation. A sale and purchase requires the following documents.

Schedule 1 (buyer’s information form)

This details ownership information relating to the park home and the park itself. Enclosed with it is the “written statement”, details of outgoings, and “park rules” (rules applicable to the park in question, which its owner has imposed).

Schedule 2 (notice of proposed sale)

This is one of the last remnants of the semi-feudal system of mobile home park governance which the MHA 2013 will help sweep away. A park owner could traditionally ‘approve’ a prospective purchaser, and without that approval, the occupier / seller would have to secure a different purchaser more to the park owner’s liking. If, as often happened, they could not do so, the result was the sale of the park home at a knock-down price to the park owner (usually exactly what the latter intended). The MHA 2013 gives park owners very little leeway. They can only object to a purchaser on very limited grounds and, more importantly, must do so within 21 days, by applying to the First-Tier Tribunal which, since 2011, has had jurisdiction to hear park home disputes.

Schedule 4 (assignment)

This is the document which effects the transfer of ownership from seller to buyer. No contract is drafted or exchanged on a park home sale / purchase. The parties eye each other across the dance floor until they are ready to dance, and away they go! How can this be dovetailed with a ‘bricks and mortar sale’ or purchase? In practice, the inherent flexibility of the park home side of things invariably saves the day. Demand may yet arise for a bricks and mortar-style exchange of contracts on a park home sale and purchase, but, to date, we have not seen it.

Schedule 5 (notice of assignment)

This is another hang-over from the old system. Whenever a park home is sold by an existing occupier, the park owner is enti-tled to a commission equivalent to 10% of the sale price. This falls to be paid by the purchaser. Schedule 5 confirms the transaction details. Upon being provided with the park owner’s bank details, the purchaser has seven days to pay the 10% commission, which they should have retained from the purchase monies.

Has it succeeded?

The system has now been up and running for 10 months. It introduces a reasonable degree of certainty into a transaction which historically had none. Long ago, I lost count of the times when it became apparent that a prospective client seeking help had purchased their park home without sufficient (or any) idea of what they were getting. The new system is mandatory, so, in theory at least, that can no longer happen.

The cynics – of whom, for good reason, there is no shortage in the park home community – are sceptical as to what the new compulsory system can achieve, but in my view any system, within reason, has to be better than none. No system is perfect – for instance, the new system does not address certain issues which have created no end of hardship for occupiers over the years – and not every potential flaw can be foreseen, but a good start has been made.

The new system works and, in my experience, has succeeded in stamping out the more blatant instances of sale blocking. Those park owners who would routinely deter prospective purchasers of privately marketed park homes now have to think twice.

It is to be hoped that the majority will now obey the law and no longer put their interests above those of the occupiers. Sadly, the vast sums of money which can be made in this industry mean that a ‘hardcore’ of unscrupulous park owners (or ‘UPOs’, as they are known) will find it very hard to change their ways. Now, these UPOs can be expected to resort to more subtle means of achieving their ends – a few examples of which we have already encountered and, thus far, successfully overcome.

How has the transition worked?

It’s been a mixed bag – part smooth transition, part chaos and confusion! Purchasers who are new to park homes want and expect to be able to have the reassurance and guidance that good legal advice provides. Some sellers, however, may well have purchased the home they now wish to sell without involving a solicitor, believing it unnecessary. In their eyes, legal advice is an expensive luxury provided by self-serving lawyers who don’t know the first thing about park homes! Dealing with an unrepresented seller (or buyer) is hard work, and irritating when you are continually asked for advice from someone who does not want to pay for it. Equally hard work are the estate agents who, trying to be helpful, effectively act for the unrepresented party, not realising this is tantamount to legal advice, for which they could be held to account.

To help overcome resistance to legal representation, my own firm has chosen to charge a low, fixed fee to our clients, which is a pleasant surprise to those from a bricks and mortar background, and a diabolical liberty to those from a park home background. A majority of those enquiring about the service we offer become clients. But how can we engage with those park home sellers and buyers who do not consult a legal professional and prefer to ‘go it alone’? Ask me in a year’s time!